By GARY ALLEY

October 2018

This month of October began with the Jewish holiday, Simchat Torah, which celebrates the end and restart of the annual reading cycle of the five books of Moses. This tradition of reading through the Torah—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy—the five most important books of Scripture in Jewish tradition, dates back before the time of Jesus. While Torah has often been translated as “Law,” that is only one aspect of its semantic domain. A wider and better interpretation for Torah would be “instruction” or “teaching,” for at its core the Torah leads and guides its followers like a good mentor.

Over time, the scope of Torah’s meaning expanded beyond those first five books to encompass the entire Hebrew Scripture or, what is popularly known in Christian tradition, as the Old Testament.[1] Jewish tradition even went as far as wedding this “written Torah” with an “oral Torah,” or rabbinic rulings, which became foundational for 2000 years of Jewish thought descending from the Mishna.

But for early Christianity, the letters of Paul and the writings of other nascent leaders became central in instructing its early followers in the life and teachings of Jesus. This collection of texts came to be called the “New Testament”[2] and became an enduring appendix for the earlier revelation of the Hebrew Scriptures.

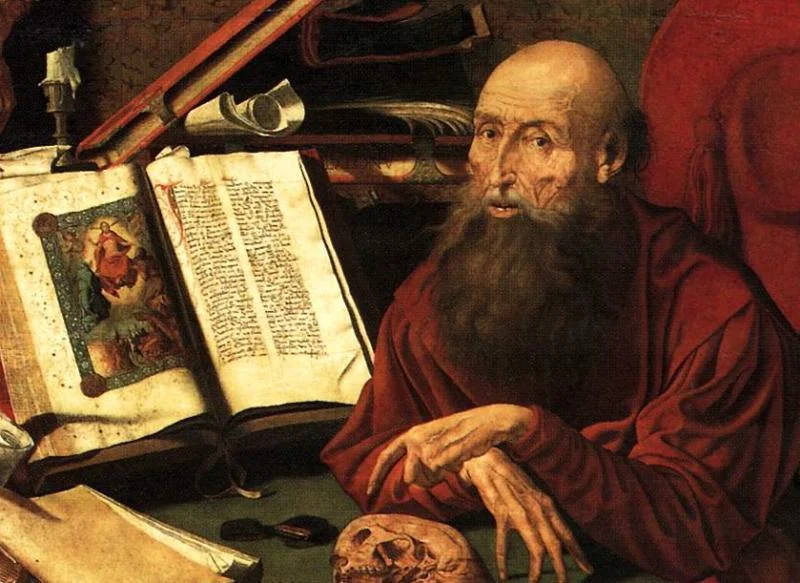

When the church father, Jerome of Stridon (located in modern day Bosnia), made his monumental Latin translation of both the Old and New Testaments, he moved to Bethlehem in order to learn Hebrew so as to translate directly from the Torah (382-405 CE). This new translation, the Vulgate, became widely adopted by the Catholic Church and would be instrumental in many other translations in Europe. In fact, the very first book ever printed on Johannes Gutenberg’s groundbreaking mechanical, movable type printing press in the 15th century was the Gutenberg Bible, a Latin edition largely following the Vulgate.

As Jerome’s Vulgate began merging the two Testaments into one bound book, these holy Christian scriptures took on a unified name—“the book,” biblos, or the Bible. With the rise and ascension of Islam in the 7th century, Jews and Christians were given the pejorative nickname, “people of the book (′Ahl al-Kitāb).” In that ancient Islamic world where literacy was the exception and not the rule, perhaps, this was veiled jealousy and admiration for the Jews’ and Christians’ tradition of hallowed texts.[3]

As Islam subsumed and reinterpreted some of Jewish and Christian written traditions, Judaism would embrace the derogatory epithet, “people of the book,” as defining their identification with the Torah. Today in Israel, at the beginning of every summer, there is a national book fair called “Shavua haSefer (week of the book)” that is an enormous display of the latest Israeli publications. This annual book bazaar is a continual reminder of Judaism’s identity with literacy that was first birthed through the propagation of the Torah.

After the invention of Gutenberg’s printing press, books and literacy spread to the masses in the West. This included the Bible. With the Reformation in the 16th century, the translating and printing of Bibles was a consistent result of Protestant work. No longer beholden to the Catholic Church’s Latin Vulgate which was no longer understood or practical for the common people, Martin Luther led the way for other Bible translations when he made the first popular German translation of the Bible in 1534. Like Jerome, he also translated the Old Testament or Torah from the original Hebrew.

In the wake of the Reformation, Bible translation became a focus for the Protestant-Evangelical movement spreading around the world in the 20th century. As we approach the end of 2018, impressively, there are now 683 different translations of the complete Bible. Yet, at least 1.5 billion people do not have a complete translation in their mother tongue. And even for those 683 languages that do have a Bible translation, the numbers do not indicate the actual quality of each mother tongue Bible.

Unlike most English Bible translations, which have been translated from the original languages, Hebrew and Greek, most Bible translations are often based on a European language Bible like English, French, or Spanish. While Jerome and Luther learned Hebrew in order to translate the Old Testament or Torah, today there is a dearth of Bible translators with a real, working knowledge of Hebrew. While there have been recent attempts to correct this Hebrew inadequacy for Bible translators and consultants, the systemic lack of attention to biblical language expertise by fervent Evangelical institutions is glaring.

This deficiency of Evangelical biblical language proficiency could be a canary in the coal mine of church-wide biblical illiteracy growing in the 21st century. Why is it that, today, most religious Jews can read some of the Torah in its original language, Hebrew, most religious Muslims can read some of the Koran in its original language, Arabic, but almost all religious Christians need translations? Yes, it can be argued that the spread of Christianity was empowered by its universal message, making it highly compatible in many cultures and languages. Yet, that strength can also be a weakness, when the shifting winds of culture and language blow back on the original biblical meaning and context. To safeguard the gospel message, a robust relationship with Hebrew and Greek are essential for the future of the Evangelical church.

May Jews and Muslims provoke us to jealousy. If we Evangelicals say Scripture is the final authority in determining faith and practice, we should prioritize its reading and learning, especially in its original languages. We are not “People of the Book” if we are not fluent in that book.

Today, we live in an unprecedented time in history with amazing access to seemingly endless information and knowledge, including insights about the Bible. But how do we weigh competing interpretations over Scripture if we do not take seriously our biblical training? Our ability to travel internationally and virtually by internet is extraordinary. If we are truly trying to follow the Lord’s teachings in the Book, we should not squander the learning opportunities that He has given us in this 21st century. Jerome’s example of coming to the Land of the Bible to learn Hebrew is even more relevant today.

[1] One of the first usages of the title “Old Testament” is attributed to the early Church Father, Melito of Sardis (died 180 CE), in modern day Turkey, which is recorded by Eusebius in Ecclesiastical History, 4.26.14.

[2] The early Church Father, Tertullian of Carthage, in modern day Tunisia (155-240 CE), was one of the first to categorize an Old and New Testament. "All Scripture is divided into two Testaments. That which preceded the advent and passion of Christ—-that is, the law and the prophets—-is called the Old; but those things which were written after His resurrection are named the New Testament. The Jews make use of the Old, we of the New: but yet they are not discordant… (Against Marcion, Book 3, Ch. 14)."

[3] “The Quran uses the term ummi to describe Muhammad. The majority of Muslim scholars interpret this word as a reference to an illiterate individual, though some modern scholars instead interpret it as a reference to those who belong to a community without a scripture.”